By Stephen Suagee

Since 2011, the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe (Lower Elwha) on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula has been deeply involved in the removal of two hydro-electric dams from the Elwha River and in restoring an ecosystem that for a century had only vestiges of any anadromous fish – the largest dam removal and fish restoration project ever undertaken in the United States if not the world.

Today the dams are down and native Elwha chinook and steelhead have begun to return to the upper watershed – a promising start to a project that the Elwha people began working on as soon as they realized the dams were coming, at a time when they were still virtual squatters in their own homeland. In the Klallam language, “Klallam” means “The Strong People,” and the Lower Elwha people needed to be exactly that in order to marshal the support needed for removal of the dams and to develop the capacity to restore the ecosystem.

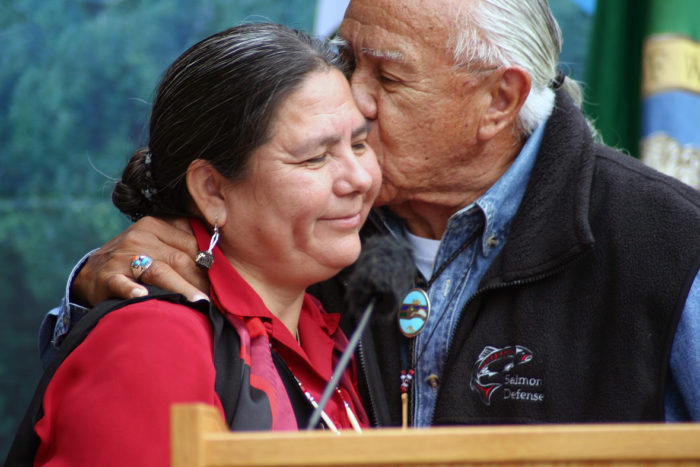

Billy Frank, Jr. (1931-2014), former chariman of Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission and posthumous recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom embraces Elwha Chairwoman, Frances Charles at the Elwha dam removal celebration in 2011. The Elwha River Restoration in the Olympic Peninsula was the largest dam removal project in U.S. and potentially world history. Photo: Richard Walker, Indian Country Today Media Network

This effort has been a quintessential exercise of sovereignty and culture. It has built on the treaty rights and other victories of the 1970s chronicled at isqmagazine.org by the Native American Rights Fund (NARF), and it applies traditional tribal values of determination, cooperation, and connectedness to the natural world to promote long-term sustainability in a post-extraction economy.

The Elwha River empties into the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the northern shore of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State, where the Tribe’s 1,000-acre land base is located. Elwha Dam was completed in 1913, at river mile 5.9, to provide hydro-power for the saw mills of Port Angeles. It immediately blocked the upper 90 percent of the watershed, over seventy miles of habitat used by famously abundant populations of all five species of Pacific salmon and steelhead, including the legendary “June hogs,” 100-pound Chinook salmon that ran upstream every summer. Populations of all these fish – the lifeblood of the Elwha people’s subsistence, culture, and economy for over twenty centuries – immediately plummeted and by the end of the 20th century hovered at the brink of extirpation (extinction within the watershed), less than one percent of what used to be. Some populations had become extinct and Puget Sound Chinook Salmon and Puget Sound steelhead had been listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Elwha Village had been a signatory to the 1855 Treaty of Point No Point – one of the treaties vindicated in the 1974 Boldt decision – in which all Klallam Indians of the Peninsula, like other western Washington tribes, ceded hundreds of thousands of acres of aboriginal lands to the United States while reserving the all-important, pre-existing “right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations.” (The court decisions have repeatedly affirmed a foundational principle of federal Indian law, that these treaty rights were not a gratuity from the United States but a reservation by the Tribes of what they always had.) So Elwha Dam effectively destroyed the one thing that Lower Elwha most needed in this treaty bargain. Adding insult to injury, Glines Canyon Dam was built seven miles upstream in 1925-27, also for hydro-power.

It took one hundred years for this small, impoverished Lower Elwha Tribe to gain the status and know-how to get the dams removed. In 1936-37, under authority of the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, the Interior Department acquired lands in trust for the Elwha Indians at the mouth of the Elwha River. Until then, the people lived mostly in shacks on timber company or County land, many on Ediz Hook, the sand spit that encloses Port Angeles Harbor. In 1938, eighty percent of the watershed was included in the newly created Olympic National Park (the interior of the Peninsula is some of the wildest and steepest country in the Lower 48, its dense forests and rock-and-ice mountains overlooking the salt water from heights well over 7,000 feet), thereby ensuring that it would remain pristine forever. In 1968, with treaty rights litigation and a new era of federal Indian law looming, Lower Elwha organized a modern tribal government with the approval of a Constitution, and had its 1936-37 trust lands proclaimed as its Reservation.

When the 1974 Boldt decision confirmed the legitimacy of the treaty fishing right, the legal and political momentum began to move in favor of fish protection for Tribes. In 1979, a coalition of Lower Elwha, federal agencies, conservationists, and sportspeople persuaded the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to assume jurisdiction over re-licensing of the dams (built before the Federal Power Act) and to consider imposing fish passage requirements. Further litigation regarding FERC’s authority was forestalled by broad stakeholder agreement that took the form of the 1992 Elwha River Ecosystem and Fisheries Restoration Act (EREFRA), in the run up to which Lower Elwha Chairwoman Carla Elofson told Senator Bill Bradley’s Subcommittee on Water and Power:

When the treaty was signed, we were promised that in exchange for giving up our land, the United States would be sure we had a safe place to live and that our fish would be protected. For at least the past 80 years since the first dam was built on the Elwha River, it has been impossible for the United States to keep its promises.

Female humpback salmon swim in the Elwha River. Photo: John Gussman, DC Productions.

It took nearly 20 more years to achieve actual dam removal. The Secretary of the Interior appointed the National Park Service (NPS) as the lead agency to implement EREFRA, to perform the studies that would determine the dams’ final fate, to acquire them and prepare for their demolition. When this writer began working for the Tribe in 2008, dam removal was not yet a certainty. The economic stimulus legislation of 2009 provided significant funds to get the project back on schedule and in September, 2011, the Tribe, NPS, and a host of partners celebrated the first breakup of concrete. It was a beautiful, festive day with speeches and invocations by the Governor, Washington’s two Senators, the Secretary of the Interior, other important officials elected and appointed, and Lower Elwha Chairwoman Frances Charles. Nisqually fishing rights icon Billy Frank Jr., good friend to the Tribe celebrated elsewhere in these pages, was there and expressed his joy and gratitude with typical directness: Freeing the Elwha “is what it’s all about….When you say the Elwha people are strong, you’re damn right they’re strong.” Former Sen. Bradley may have best captured Lower Elwha’s role:

We know what the River wanted because it always had a voice…The Lower Elwha Klallam tribe, its leaders and members, cared for the River, lived from the river, and brought the River’s voice to every audience that could be found.

Each of us owes the…Tribe the greatest possible gratitude for their unceasing efforts over decades…[and]…the greatest deference and respect for the burdens its people and society have borne because of what was done to the River 100 years ago.

Glines Canyon, post-dam removal. Photo: John Gussman, DC Productions.

Glines Canyon, after dam removal. Photo: Joel Rogers.

So down came the dams within two years, which began the discharge of over 24 million cubic yards of accumulated sediments during high water events, creating peril for fish both large and tiny. The coalition of tribal, federal, and State restoration planners had anticipated this peril; to meet it, the Tribe built the House of Salmon hatchery to ensure preservation of native Elwha fish stocks in the event the sediment discharge were to wipe out what remained in the river. Indeed, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) would not have approved dam removal under the ESA had the House of Salmon not developed its native Elwha fish programs.

There is still much to do to restore the watershed and the fishery; in fact, the restoration process is still considered to be in the first of four phases – the preservation phase. Rubble and remnant boulders must be blasted away so that the salmon species that do not leap can come upstream and contribute their spawned-out carcasses to the nutrient cycle. Significant volumes of sediment will continue to flush downstream, but a more beneficial consequence of that sediment to date has been the establishment of over 80 acres of new beach at the estuary (along with the new legal question of who owns what part of it). The Tribe’s award-winning stream rehab crew (which includes displaced loggers and heavy-equipment operators) will continue to construct engineered log jams and other habitat improvements on the newly liberated river as its carves its new course through the former reservoir areas, the lower flood plain, and the new estuary. The House of Salmon will need to adapt to the phases of restoration yet to come and the voluntary tribal and non-tribal harvest moratorium will eventually give way to renewed utilization of the fish that have always been the Tribe’s lifeblood.

Elwha dam removal has been about the Tribe developing the sovereign capacity to restore and protect what is most important to the Tribe, a case study in the institution-building made possible by victories like the Boldt decision. But that institution-building has always been informed by the values of a culture that would not die. Dam removal and fish restoration is about restoring the role of the indigenous decision-makers in the management of the river that has always been their home. The fish have always been there for the Strong People and the Strong People have now been there for the fish when the fish most needed them.

Stephen Suagee is the general counsel for the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe.